Ever since the summer of 2020, when German payments giant Wirecard collapsed after failing to account for €1.9 billion in missing assets, its former COO Jan Marsalek has been a wanted man. The Insider previously traced Marsalek to Russia, where the Austrian national enjoys a colorful life under the protection of the Kremlin’s security services. After making minor alterations to his appearance via cosmetic surgery, Marsalek freely walks around central Moscow accompanied by his new girlfriend, an FSB employee. Initially recruited by the GRU, Marsalek has recently been cooperating extensively with the FSB, making frequent appearances at the Lubyanka. In addition, Marsalek regularly travels to the occupied territories of Ukraine to carry out “combat missions” – accompanied by soldiers of the Russian special forces.

Content

From Munich to Lubyanka

His coy mistress

Facials, hair plugs, soldier, spy

The fugitive

The London spy ring

Red Sparrow

Show me the money

This is a joint investigation with Der Spiegel.

“So I tested the facial recognition system installed in Moscow and it works fabulously well,” Jan Marsalek wrote in a Telegram chat on October 7, 2021. The German payments giant Wirecard had collapsed fifteen months prior, and its fugitive former chief operating officer was already ensconced in Russia, remarking on his new life as a defector to his former business associate, Orlin Roussev. Marsalek would later suborn the Bulgarian as an agent of Russian intelligence, spying on U.S. military installations in Europe and plotting to kidnap Putin-critical journalists and Kazakhstani dissidents from a base of operations two-and-a-half hours north of London. “Really scary,” Marsalek wrote about the newly installed, FSB-run panopticon CCTV surveillance system in the Russian capital, euphemistically called Safe City. “The question is how to trick such systems in the future.” As Europe’s most wanted man, Marsalek was desperately trying to stay off the grid. He failed.

Nearly four years later, on the afternoon of July 1, 2025, Marsalek appeared perfectly relaxed as he strolled across Moscow’s Trubnaya Square. Neatly bearded, with a close-shaved head, khaki drawstring pants, and sunglasses dangling from the collar of his white tee, Marsalek looked the very picture of unencumbered summer leisure. In one hand, he held his cellphone; in the other, the outstretched palm of his slim, athletic redhead girlfriend. It was hard, just from a quick CCTV snapshot of him, to discern which was his more constant companion: the phone, or the woman who had been his Russian language teacher in the early years of his acclimatization to Russia. One thing had led to another (they always did with Marsalek) and the two had become a couple, not just romantically but also professionally. Tatiana Spiridonova had everything someone in Marsalek’s position could have wanted: a diplomatic passport and a reason to travel to a vaguely European country, Turkey, given her fluency in the language and job as a professor of Turkish at Moscow State University. These items on Spiridonova’s CV also made her the perfect errand girl for the FSB, the Russian intelligence agency Marsalek was now working for. “Girls are ideal,” Marsalek once wrote to Roussev as he was planning for Tatiana to ferry highly sensitive laptops stolen from the Austrian intelligence agency. “They look innocent”.

The fallen fintech wizard was relaxed in that snapshot because he thought he had finally tricked the ubiquitous Safe City. For one thing, his face looked different. He had once written to Roussev, who is now serving a 17-year prison sentence in the United Kingdom, that he had undergone several plastic surgeries to make himself unrecognizable. He had grown a beard and had a hair transplant. What Marsalek didn’t realize, however, was that despite his best attempts at metamorphosis, a group of investigative journalists – two of whom he’d spent hundreds of thousands of dollars surveilling and trying to kidnap – had been watching his every move in Moscow, almost in real time, for over a year. Not only that: they were using the same surveillance system run by the Russian special service Marsalek was working for.

From Munich to Lubyanka

Marsalek, 45, had once been the chief operating officer and a board member of Wirecard, the Munich-based and DAX-registered German financial services giant, which collapsed in Madoff-like ignominy in 2020. Billions of euros went missing, and so did he.

As an investigation by The Insider and Der Spiegel disclosed last year, Marsalek had been recruited over a decade ago by the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence service, during his stratospheric ascent as one of Central Europe’s business wunderkinds. He had opened doors for the GRU in Libya and used millions siphoned away from Wirecard to fund Russian military operations in Syria. In June 2020, when Wirecard came crashing down, he seemed to disappear from the face of the earth. But while German authorities – along with most of the rest of the world – were looking for Marsalek in Asia and Africa, The Insider had promptly discovered digital traces in Belarus, and from there on to Russia. Marsalek had been spirited away by former officers of Austria’s domestic intelligence agency whom he himself had recruited and kept on his personal payroll.

Marsalek had opened doors for the GRU in Libya and used millions siphoned away from Wirecard to fund Russian military operations in Syria.

Now there are good grounds to believe Marsalek works for the GRU’s civilian and domestic counterpart, the FSB, modern Russia’s heir to the Soviet KGB. He has certainly been busy. In December 2024, Marsalek was named as the ringleader of a network of six Russian spies convicted in a London High Court of plotting to kidnap and assassinate dissidents and investigative journalists, including two of the writers on this piece.

Marsalek has spent the last five years living in Russia under multiple identities, including those of two Orthodox priests. In that time, he has carried a series of passports, both real and false – all issued under the patronage and protection of Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin. He remains untouchable, it seems, for the European investigators, prosecutors, and intelligence services who are looking for him. Unfindable, too, if one is to judge by the constant use of the disclaimer “reportedly” appended to European law enforcement agencies’ description of his suspected whereabouts.

Yet a team of investigative journalists from The Insider, Der Spiegel, ZDF, and the Austrian Der Standard managed to track him down in central Moscow and follow him for more than a year, reconstructing his movements and travel patterns using a combination of travel data, mobile phone metadata, and CCTV footage.

Like many blown Russian assets no longer able to operate in the West, Marsalek lives a fairly mundane and unglamorous life in the Motherland – albeit one punctuated by occasional flashes of adventure. Marsalek takes regular, 27-hour long trips to Russian-occupied Crimea. The Insider has found ticketing data for at least five such sorties since 2023, and on many of them he has been accompanied by special forces commandos of the Russian Spetsnaz. His phone occasionally pings near the Russia-Ukraine border, and official records show he made at least one dangerous visit to the Ukrainian frontline in Russian-occupied Mariupol as part of a sabotage unit of the Russian army.

Most mornings, when he isn’t with Spiridonova or whizzing past the Kremlin on an electric scooter (he was once fined for “endangering public safety” due to riding on the pavement in central Moscow), Marsalek passes the barriers of Moscow's Lubyanka metro station, the casualwear replaced by a more funereal outfit: a black suit, black tie, and black oversized glasses. Under his left arm, he clutches a MacBook and a leather-covered notebook. His shaved head, one can see more clearly from this higher-resolution CCTV footage, betrays a suspiciously newborn hairline with large bald patches behind it. In early 2024, Marsalek’s phone pinged frequently next to a hair transplant clinic in Moscow. As with most things in today’s heavily sanctioned Russia, follicular unit extractions are a roll of the dice.

His coy mistress

Anyone looking to get close to Marsalek needs to go through his girlfriend.

Born on January 24, 1984, Tatiana Spiridonova studied Orientalism at the Institute of Practical Oriental Studies in Moscow. She is a member in good standing of the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society, which was founded in 1882 to foster positive relations between Russia and the Middle East. It is also a cut-out, according to Western intelligence, of the Russian secret services. The head of the Society is a former director of the FSB.

Spiridonova's proximity to the government is also evidenced by leaks from a Moscow administrative database. As an authoritarian surveillance state, Russia may be excellent at collecting data on its citizens, but like many regimes of its kind, corruption is a defining characteristic of both the petty and not-so-petty bureaucracies of Putinism. Almost everything is for sale – from tax returns and auto insurance forms to property deeds and flight itineraries. That makes Russia, paradoxically, one of the most transparent countries on the planet.

So it was that The Insider and its partners were able to find out so much on the subject of Spiridonova, right down to the forms she submitted to the Moscow database in order to obtain a biometric passport. Her profile notes that she had a security clearance for confidential information for several years, until it was classified “top secret.” She had previously also held a diplomatic position at the Russian Embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan.

Tatiana Spiridonova

Tatiana Spiridonova

Tatiana Spiridonova

Marsalek met Spiridonova in 2021, about a year after his defection from Munich. Both have a mutual acquaintance, Stanislav Petlinsky, the GRU officer who recruited Marsalek eleven years ago.

In the spring of 2024, reporters from Der Spiegel sat down with Petlinsky at Jumeirah al-Naseem beach resort in Dubai. He denied that Marsalek was ever his agent, just a dear friend. Petlinsky, a charismatic, soft-spoken middle-aged man of a sturdy, fit build, was fond of talking about the former Wirecard manager and their close relationship, which coalesced on July 6, 2014, when the two met on a boat in the south of France.

Marsalek, Petlinsky told Der Spiegel, was “super precise, a bit autistic even.” Human relationships are “not Jan’s greatest strength,” Petlinsky added. “He lacks empathy.” A lack of empathy is the telltale sign of the sociopath, and also a fine starting point for a mole or deep-cover operative.

Petlinsky is very likely the person who introduced Spiridonova to Marsalek, possibly as the latter’s Russian language instructor. Marsalek later put her to work as a courier for his clandestine operations.

In June 2022, Marsalek targeted influential Austrians by means of a spy network he built up in Vienna. Through Egisto Ott, a contact in Viennese security circles, Marsalek’s helpers obtained the smartphones of three former high-ranking employees of the Austrian Ministry of the Interior.

On June 10, 2022, a courier from the agent network received the three cell phones in Vienna. From there, he smuggled them to Istanbul, and on June 11, Spiridonova traveled from Moscow to Turkey to collect them, according to secured chats and leaked flight and mobile phone data obtained from Russia.

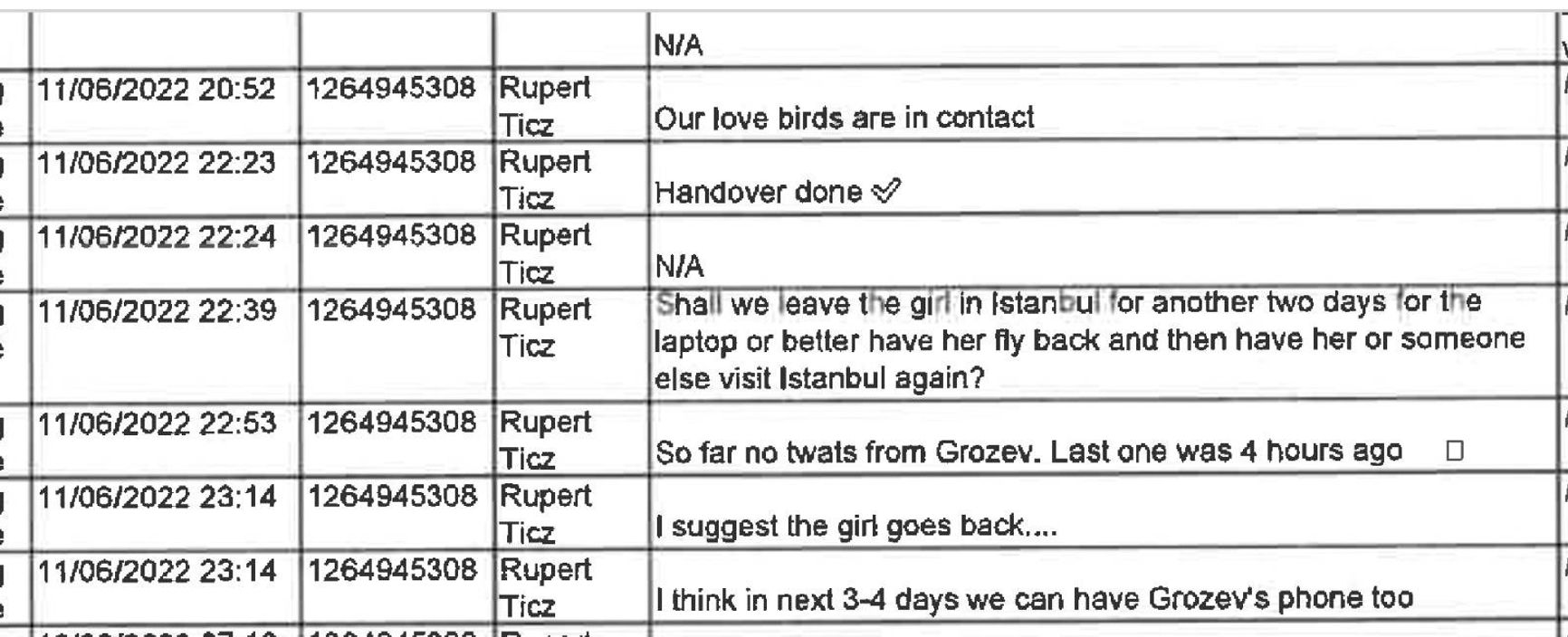

Jan Marsalek ("Rupert Tisz") chatting with Orlin Roussev during the handover of stolen phones to Tatiana Spridonova.

Source: Metropolitan Police (UK)

“The girl has just landed,” Marsalek wrote to the Viennese courier on the same day in a Telegram chat seen by The Insider. In the hours that followed, Marsalek pondered whether she should fly back immediately to Moscow with the stolen telephones or wait in town for another prized delivery. On that same day, a different group of operatives supervised by Marsalek had broken into the Vienna apartment of one of the present writers, Christo Grozev, the head of investigations at The Insider, and had stolen what they falsely believed was his work laptop. (In fact, this was a decommissioned computer, which Grozev hadn’t used in five years.) “I would rather keep the girl there until the laptop arrives,” Marsalek messaged the courier. “[D]on’t want to delay Grozev’s laptop delivery in case he has some time-sensitive accounts that he may change the passwords of.”

Ultimately, Marsalek and Roussev decided it wasn’t worth Spiridonova’s time to wait for the laptop. So “Sofia,” as she was known to the spy ring, returned to Moscow on June 13. A little later that day, her cell phone logged on in the immediate vicinity of Lubyanka. Marsalek wrote to Roussev on June 14, “The FSB are shocked by the wild events in Montenegro,” apparently code for describing the contents of one of the stolen phones.

Two weeks later, June 30, Spiridonova went back to Istanbul. This time she flew in to pick up Grozev’s laptop and delivered it back to Moscow. Marsalek would later complain to Roussev that “our friends did not find anything of value” on the device.

Months later, Spiridonova traveled the same route again.

On December 13, Spiridonova flew to Istanbul, staying just long enough to receive a highly sensitive laptop, containing a NATO-compliant encryption system named SINA, that had been procured through Marsalek's helpers in Vienna. A day earlier, Marsalek had announced the arrival of his girlfriend to a contact of the agent network: “Where should my girl go when she has landed?” he messaged his contact. After initially discussing a brush-pass handover at the airport without passing customs, ultimately they decide to send Tatiana into town to meet with the couriers. “She will contact them from the same Sofia account on Telegram”, Marsalek instructed the ring-leader, Roussev. The next day, Marsalek reported the success of the operation. The laptop was “in a car on its way to Lubyanka,” he wrote. Using phone metadata bought from the Russian black market, The Insider was able to corroborate Marsalek’s words, tracing Spiridonova’s phone from her home in Moscow to the airport in the early hours of December 13, 2022, then from Istanbul airport to the hand-over place at a hotel in the city, and, finally, back to Moscow that night. Arriving at the Russian capital’s Sheremetyevo airport at 10 p.m. on December 13, the phone pinged along Moscow roads all the way to the FSB headquarters in Lubyanka Square, where its last ping was registered at half past midnight.

Tatiana Spiridonova was married when she met Jan Marsalek. But by early April 2022, she had filed for divorce, court records show.

Spiridonova’s apartment in the south of Moscow is in an unremarkable neighborhood, on Stremyannyy Pereulok. There’s a yoga studio in the back yard, diagonally opposite a business university. The plaster is peeling off the white-yellow façade of the three-story building.

Marsalek visits her there often.

On June 13 and on June 15 this past summer, footage from a surveillance camera shows him at her front door. The lens is built into the steel entrance gate of the house and provides perfect images: Marsalek was at the door in the fall of 2024, looking downcast with a woolen hat and scarf. In summer he was there again, this time cheerier with a trimmed beard, smiling as he looked up. Perhaps Tatiana was greeting him at the window.

Facials, hair plugs, soldier, spy

Flight information and ticket bookings, courtesy of leaked travel databases, show that Spiridonova often travels with Marsalek under one of at least six of his assumed identities in Russia.

As The Insider reported in March 2024, Marsalek has posed as two different Russian Orthodox priests, Konstantin Baiazov from Lipetsk, and Vitaliy Malkin from the Russian town of Vladimir. In addition, he’s used a forged Belgian passport issued in the name of Alexandre Schmidt, bearing the number #ВМ1987399 (the real document belongs to a 61-year-old Belgian national named Robert Leonard de J.). On Dec. 28, 2024, Spiridonova took the train from Moscow to St. Petersburg traveling alongside “Alexandre Schmidt.”

Yet another alter ego is “Alexander Nelidov,” whose passport says he was born on February 22, 1978 in Riga, Latvia. He obtained his Russian citizenship courtesy of Law N 5-ФКЗ, which bestowed citizenship on all citizens of the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic following the sham accession referendum of October 2022. Prior to that, “Nelidov” had been a Donbas-residing Ukrainian, his passport file claims. Except that no such Ukrainian ever existed – or, at least, none did before the Russian intelligence services got control of the public records in Donbas, allowing them to retroactively mint unlimited numbers of fake new identities.

On paper at least, “Nelidov” resides at Moscow’s Tolbukhina Street, House 7, Apartment 1, Room 54. However, the real resident of that apartment is a retired woman who lost her husband a few years ago.

On July 3, 2023, Spiridonova flew back to Moscow from the Russian resort town of Mineralnye Vody with her then 15-year-old son. Marsalek was with her under his Nelidov passport.

It was this fake persona and its consistent travel alongside Spiridonova on various flights and train rides that allowed The Insider and its consortium partners to track down Marsalek in Moscow. For Nelidov, a phone number was listed as a contact option for booking a flight in the summer of 2023. The number is also linked to Nelidov in a Russian insurance database. It was also the contact given to police during that pesky encounter where, at 9 p.m. on April 8, 2024, he was fined for driving his scooter on the sidewalk of a street one minute’s ride from the Kremlin. Just two years earlier, Marsalek had boasted to Roussev that he carried a letter from the FSB allowing him to avoid restrictions reserved for other mortals. In April 2024, with Roussev and his gang in British custody and Marsalek's embarrassing correspondence with them – including this boast – in the hands of Western investigators, perhaps the FSB had revoked their get out of jail free card.

Marsalek's fake identity as “Alexander Nelidov” and his consistent travel alongside Spiridonova on various flights and train rides allowed The Insider to track down Marsalek in Moscow.

At the beginning of September, Der Spiegel and ZDF called the number via the messenger service Telegram. The avatar on the account was a cartoon bear in sunglasses – a little on-the-nose for a Russian intelligence asset but certainly consistent with Marsalek’s playful standard for plausible deniability. The call was declined.

The reporters next tried a text message. “Tell me who I'm talking to, please?” came the reply in fluent Russian. When asked if the person on the other end of the line was really Jan Marsalek, the account answered: “You have made a mistake.”

Yet the conversation didn’t end there. Further messages on Telegram yielded curt, interrogative replies — “What exactly do you want to talk about?” For starters, why did Marsalek spy on Christo Grozev and Roman Dobrokhotov for the FSB? After a long pause came the uninformative reply: “Very interesting characters.”

Asked if Nelidov-Marsalek would prefer speaking on the phone, the account answered: “A very interesting offer.” Then the exchange broke off.

Once you have a phone number in Russia, you have the ability to track its user’s movements, again using leaked data. Every time the phone dials into a radio cell, the location of the tower is recorded.

And if you transfer that information onto a map, you can see where Jan Marsalek has gone under the guise of Alexander Nelidov.

The patterns are spotty due to the fact that he isn’t using the Nelidov phone every day. In fact, weeks can pass without it pinging a cell tower in Russia. Nevertheless, after a long enough period of time – in this case, several months – The Insider’s investigators were able to show a cluster of log-ins at several places in Moscow, with a radius of a few hundred meters.

Nowhere was the Nelidov phone logged in more often than in the area of the FSB headquarters on Lubyanka Square. A radio mast detected the device there 304 times between the beginning of January and late April 2025.

Marsalek’s travel to the vicinity of the FSB headquarters was corroborated by photographic evidence – snapshots from CCTV cameras which caught him coming and going.

These show Marsalek commuting during normal office hours near the FSB headquarters, well dressed and arguably, on his way to his new occupation in service of the Russian security service.

But if Lubyanka Square is where he goes to work, where does he live?

An exact address cannot be determined based on the data The Insider has analyzed, and the registration address on the western edge of Moscow entered in the Nelidov passport documents is clearly a feint. Perhaps Marsalek doesn’t keep his own apartment for security reasons and is instead constantly on the move, but with Spiridonova, he at least has a fixed point of contact. Sometimes, it appears from the pings left by his phone, he stays in an Ibis Hotel just around the corner from her apartment. (The hotel address was provided by “Alexander Nelidov” as his current address for health insurance purposes, found in a leaked insurance database.)

More often, phone pings show, Marsalek seems to be drawn to a hotel that is more in line with his former high-flying habits: the five-star Swissotel on the Moskva River, complete with a rooftop bar, spa, and beauty salon. Notwithstanding his bad hair transplant, Marsalek attaches great importance to his appearance, according to his past and present associates. At the beginning of 2024, the Nelidov phone logged in at the Swissotel location 56 times within the space of seven days.

As for the spotty hairline restoration, Marsalek may well have gone to the Institute of Plastic Surgery in the north of Moscow. On its website, the clinic advertises cosmetic procedures of all kinds, including those of the sort that would explain the fugitive’s altered appearance. His phone logged into a radio mast used by the telephone to the clinic on March 8, 2024.

A riskier undertaking than that elective scalp surgery was Marsalek’s decision to travel to an active warzone in Ukraine.

According to location data, the Nelidov phone logged into the train station at the Russian border town of Mitrofanovka at 10:08 a.m. on February 21, 2024, after twelve days of radio silence. It is only a few kilometers from this spot to Russian-occupied eastern Ukraine, within striking range of Kyiv’s growing arsenal of long-range missiles and drones. Marsalek's presumed journey home to Moscow can be traced along the railway line via Voronezh and Lipetsk. Around 11 p.m., the cell phone was back at the five-star Swissotel. Maybe a little spa treatment after a tough few days at the front?

Photos show the ex-Wirecard manager in full military combat gear, complete with a balaclava and a “Z,” the Russian war symbol, sewn onto his protective vest.

Leaked information from Russian border surveillance indicates other trips by Marsalek to Ukraine. On November 22, 2023, his Nelidov persona traveled from Mariupol, in Ukraine’s southeast, to Crimea. The picture stored in the border crossing computer system is quite clearly that of Jan Marsalek.

Russian security sources have told The Insider that Marsalek is now on combat duty. He’s taken at least five train trips to the occupied Ukrainian peninsula, each nearly 30 hours long. Among his co-travelers is Lieutenant Kirill D., a member of the Spetsnaz.

Russian security sources have told The Insider that Marsalek is now on combat duty. He’s taken at least five train trips to occupied Crimea.

All his train tickets to and from Crimea are purchased via tradecraft reserved for members of Russia’s army and security services: seats on the train are initially booked in the name of young children, between one and five years old, usually born in Crimea. The tickets are then repurposed just hours before the trip to the actual passenger – in Marsalek’s case, to “Alexander Nelidov.” The purpose of such tradecraft is likely to keep travel plans for Russia's military hidden from Ukrainian intelligence services.

Europe’s most wanted man, it is highly likely, is now a Russian combatant in Europe’s largest land war since World War II.

The fugitive

Germany’s Federal Prosecutor General is officially investigating Marsalek for secret service agent activity. The Munich Criminal Police and the Federal Criminal Police Office, for their part, have been trying to get hold of him for years. But police and intelligence officers alike remain largely in the dark regarding Marsalek's activities in Russia.

Their options for gathering information are limited. The police investigators are the spearhead of the German fight against crime; they look for murderers and serious offenders, but they only take on about 500 cases a year. The Insider was able to confirm Marsalek’s whereabouts using the facial recognition program PimEyes on Facebook. However, German police officers are still not allowed to use this software due to data protection concerns.

What they have at their disposal are the classic methods of forensic work: they can listen to conventional telephone calls, which Marsalek hardly ever makes. They are allowed to observe relatives and friends of wanted persons, whom Marsalek is unlikely to visit. They are able to look through social media, which Marsalek does not use. In short, they lack the requisite access to make much headway in his case.

Cooperation with the intelligence services is also said to be difficult, according to information compiled by Der Spiegel. “They are not very interested in the case,” noted an investigator in a confidential conversation.

Nor is the Russian government providing any assistance to Berlin, not a surprise given Germany’s ongoing security assistance to Ukraine. Officially, the Kremlin has no knowledge of Marsalek's whereabouts. (Unofficially, the Kremlin can see his movements around Moscow and Russia live, just as this investigation team can.)

The hopes of the German authorities are therefore focused on Marsalek turning himself in voluntarily at some point, once he can no longer bear the stresses of life on the run. Or that a search notice from Interpol distributed worldwide leads to success. “Maybe one day he will go on a trip where he will be recognized,” said one German official from Bavaria. “We can wait.”

The same, however, cannot be said by those whom Marsalek has targeted with kidnapping – or worse.

The London spy ring

In March, a London court found the aforementioned Roussev and five other Bulgarians guilty of spying for Russia in Europe between summer 2020 and February 2023. According to the information collected by Scotland Yard and British intelligence, Marsalek was the orchestrator and financier of this international plot.

Probably never before have the activities of secret agents been so well documented as in this case.

The main perpetrator is Bulgarian national Orlin Roussev, an old business contact of Marsalek’s from back in the Wirecard days. Roussev and the other Bulgarian confidants put together a total of at least six European-wide agent networks, based out of London. On the confiscated cell phone of the Bulgarian, more than 100,000 revealing chat messages between Roussev and Marsalek were later found. With this and other evidence, the British authorities were able to reconstruct the spy ring’s activities.

In the fall of 2022, for example, the group spied on a U.S. military base in Stuttgart, Germany. The agents boasted expensive technology capable of monitoring cell phones, but after their connection to Moscow was discovered, British counterintelligence was hot on their heels. In February 2023, police stormed several apartments in England and arrested the Bulgarians.

According to the court, 495 SIM cards were found during the raid, along with more than 200 telephones, 258 hard drives, eleven drones, 75 different passports, and various listening devices – some hidden in everyday objects such as toys or ties.

Several digital copies of forged identity documents were also discovered. Among them: the Belgian passport in the name of “Alexandre Schmidt” bearing Marsalek's photo.

As the chats show, Marsalek was obsessed with getting his hands dirty on behalf of his Russian protectors. “We have to kidnap someone and bring him back to Russia,” he wrote to his Bulgarian helper in September 2021, setting his sights on a former Russian security official who had fled to Europe. “It doesn't matter if he dies by accident,” Marsalek continued, “but it would be better if he made it to Moscow.”

Marsalek was obsessed with getting his hands dirty on behalf of his Russian protectors. “We have to kidnap someone and bring him back to Russia,” he wrote to his Bulgarian helper in September 2021.

As requested, Marsalek's Bulgarian agents traveled to Montenegro in the fall of 2021, observing the target there for weeks. According to the chats, Marsalek's spy ring met a second armed team of agents on site – this one led by a mysterious FSB spy whom the British press simply called “Red Sparrow,” a reference to female Soviet intelligence agents whose main tactic of tradecraft was seduction. However, direct support from Moscow was needed for the delicate mission, and the kidnapping/exfiltration failed at the last minute. Today, the ex-official who was targeted is hiding in an unknown location.

But Marsalek’s band of Bulgarians pressed on, targeting two of the authors of this article: Christo Grozev, the head of investigations at The Insider, and Roman Dokrokhotov, the outlet’s editor-in-chief.

Grozev was formerly lead investigator and later managing director for the investigative platform Bellingcat, where he helped unmask the poisoners of Sergei Skripal and Alexei Navalny while also charting the route Marsalek took out of Germany and into Russia. Dobrokhotov fled Russia and now lives in Europe, with a Kremlin-issued arrest warrant hanging over his head.

Marsalek's contract agents followed both journalists around Europe. They rented an apartment close to Grozev’s Vienna residence, using cameras to observe the investigator and his family. Reports and files with video recordings regularly ended up with Marsalek and his Moscow intelligence associates, the London High Court found. According to seized chats, Marsalek and the Bulgarian gang leader also considered whether Grozev could be kidnapped or arrested in order to obtain his cell phone and laptop.

The men even chatted about a possible murder of the reporter. Using an axe for this is a thing of the past, Marsalek said in a message to the Bulgarian in December 2022. “Better is a sledgehammer, Wagner style” – an allusion to war crimes committed by the Russian mercenary group in Ukraine and Syria. Marsalek, however, decided against the murder plot. In the end, the lower-order kidnapping was still uncovered by the British domestic intelligence service MI5.

According to the court documents, Marsalek was willing to pay a lot for the work of the Bulgarians. Between 2021 and 2023 alone, the equivalent of more than 200,000 euros is indicated to have flowed from him to Roussev, disguised via accounts of front companies. According to the British authorities, at least part of the money comes from the Russian secret service. The provenance of the rest can only be guessed at.

Red Sparrow

And who is the FSB spy “Red Sparrow” referred to in Marsalek’s Montenegro kidnapping mission chats?

The Insider was able to identify her thanks to documentation accompanying Marsalek’s application for a passport in the name of Konstanin Baiazov, one of the two Russian Orthodox priests whose identity he’s co-opted. Yevgenia Kurochkina is entered in one of the documents as the person applying on his behalf; her telephone number is also included. Using that number, The Insider was able to establish that she regularly travels with and places calls to a particular Moscow agent of the FSB.

The data also shows that Kurochkina was the one who shepherded Marsalek to Crimea, his first hiding place after fleeing Germany in 2020.

At the end of December 2021, the London court found, the Bulgarian team of agents entrusted with the kidnapping in Montenegro anticipated the coming of “Red Sparrow” before the New Year. And sure enough, Russian flight data shows a booking for December 29, 2021 from Moscow to Montenegro via Istanbul for none other than Yevgenia Kurochkina.

It is hard to imagine that her trip to the Balkans at the same time as the heralded arrival of “Red Sparrow” was just a coincidence. Kurochkina was the right person for the job, as evidenced by her own curriculum vitae. Starting from at least 2006, she worked as a personal driver and bodyguard for business bosses, and also for a former Ukrainian government member. Kurochkina’s special skills include “hand-to-hand combat techniques,” “external surveillance,“ and “the use of firearms.” Private photos show her shooting an assault rifle with the confidence of someone who has handled such weapons before.

Even more telling, this highly capable 41-year-old works as a bodyguard and assistant to Stanislav Petlinsky, Marsalek's recruiter-handler in the GRU.

Show me the money

The Wirecard scandal is first and foremost a financial one. The German answer to PayPal, boosted by traders and the international press as an international economic giant, was once thought of as the fintech company of the future, more valuable than Deutsche Bank. Traded on the DAX-30, it boasted a valuation of $28 billion. Then came June 2020, when, in the midst of an audit, Wirecard could not locate €1.9 billion in assets it claimed were being held somewhere in the world — Russia, the United Arab Emirates, or the Philippines. In fact, the money didn’t exist. Wirecard’s worth was predicated on commissions supposedly earned from three companies: Al Alam, Senjo, and PayEasy, based in Dubai, Singapore, and Manila, respectively. Wirecard money flowed into all three, but as the defunct company’s imprisoned former CEO Markus Braun claims, it was then funneled away into a complex web of offshore accounts controlled by his then number two, Jan Marsalek.

To this day, the €1.9 billion has not been found. Was it siphoned off by Marsalek and his co-conspirators to some offshore hideaway, or was it simply never there – the stuff of imaginative fiction, rather like Marsalek’s new public-facing existence as one of Vladimir Putin’s secret soldiers and spies?

There is fragmentary evidence of at least some of the funds being removed – to Singapore, Switzerland, Scotland, and of course Russia.

In Moscow, mobile phone data records can be used to determine a possible house bank of Marsalek. From the FSB’s headquarters, it is only a ten-minute taxi ride to a branch of the Transkapitalbank in the east of the city. The U.S. Treasury Department, which has sanctioned Transkapitalbank, has described the financial institution as the “heart” of the Russian sanctions evasion efforts that have kept the Kremlin’s war machine in Ukraine humming along.

A radio mast stands less than 60 meters away from the Moscow branch. From late January to the end of May 2024, Marsalek's phone was recorded there 104 times.